Second Valley jetty in the 1960s, looking north towards Normanville.

In this special guest post, Joel’s dad Jeff Catchlove shares some of his memories and photographs from camping trips to the South-Western Fleurieu in the 1950s and 60s.

Second Valley has always been close to my heart. I’ve just turned 70 and reminiscence is inevitable. Our childhood was unencumbered – most of us were poor, though we didn’t know it. There was no TV but we just as eagerly listened to Biggles, Hop Harrigan, the Goons and Hancock’s Halfhour on ‘the wireless’. We also played outdoors every day, both at school and at home. Children’s books were limited to Enid Blyton, Captain W E Johns and Eagle or Daily Mail Annuals. We dressed in suits to go to ‘town’ on the trolley bus or train and the family acquired its first car when we were ten or so years old. That revolutionised the possibilities of where we could go as a family. Our FJ Holden quickly ushered in trips to Mt Gambier, the Great Ocean Rd, even Queensland so my dad and we could visit his Air Force mates again.

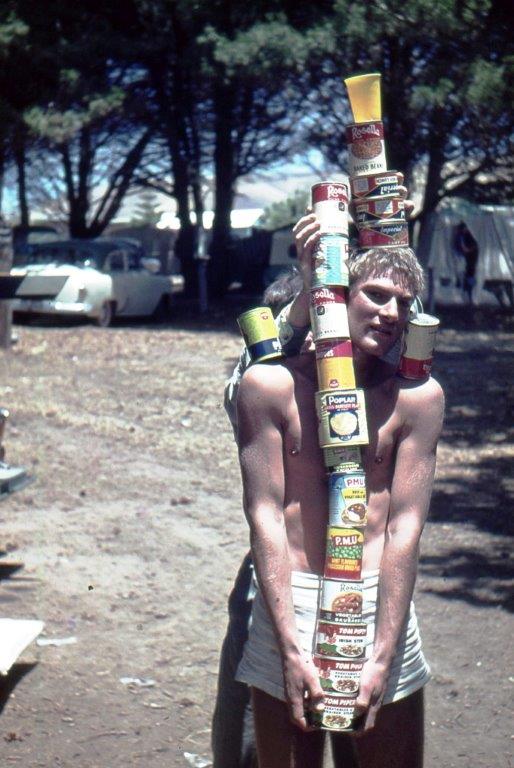

Camping at Second Valley in the 1960s, complete with a week’s worth of rations.

After a year and a half, we’ve finally got to developing a visual identity for the farm. While our working name for the farm, “Trees, Bees and Cheese”, is more conceptual than place-based, we wanted the logo to reflect some of the distinctiveness of the farm’s landscape.

After a year and a half, we’ve finally got to developing a visual identity for the farm. While our working name for the farm, “Trees, Bees and Cheese”, is more conceptual than place-based, we wanted the logo to reflect some of the distinctiveness of the farm’s landscape.

In The Biggest Estate on Earth (Allen & Unwin, 2011), historian Bill Gammage describes a detailed vision of Aboriginal land management prior to European colonisation of Australia. While many Australians have a broad sense that “fire-stick farming” was (and is) a tool used by Aboriginal people, The Biggest Estate on Earth begins to fathom how finely tuned Aboriginal fire use was. With fire as one of a suite of tools, Aboriginal people across the Australian continent carved the landscape into a mosaic of ecosystems, each harbouring plants and animals of differing sensitivity to fire, each maintained to maximise ecological diversity and each nested within the other to increase the ease of hunting or harvesting. For Gammage, Aboriginal land management across the continent was directed by three main principles: “ensure that all life flourishes; make plants and animals abundant, convenient and predictable”; and to “think universal, act local”.

In The Biggest Estate on Earth (Allen & Unwin, 2011), historian Bill Gammage describes a detailed vision of Aboriginal land management prior to European colonisation of Australia. While many Australians have a broad sense that “fire-stick farming” was (and is) a tool used by Aboriginal people, The Biggest Estate on Earth begins to fathom how finely tuned Aboriginal fire use was. With fire as one of a suite of tools, Aboriginal people across the Australian continent carved the landscape into a mosaic of ecosystems, each harbouring plants and animals of differing sensitivity to fire, each maintained to maximise ecological diversity and each nested within the other to increase the ease of hunting or harvesting. For Gammage, Aboriginal land management across the continent was directed by three main principles: “ensure that all life flourishes; make plants and animals abundant, convenient and predictable”; and to “think universal, act local”.