Tags

biodiversity, design, ecology, farm, gardening, nature, permaculture, planning, revegetation, water

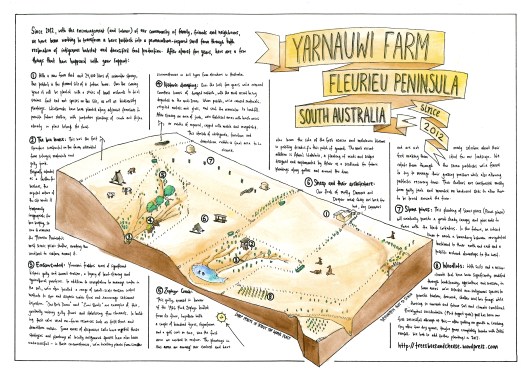

In November 2024, Joel spoke at the South Australian Permaculture Convergence about the development of Yarnauwi. This is an edited version of the talk. Thanks to Permaculture SA for their organisation of this event.

We have a notebook, where we’ve recorded quotes from our children from when they were very young. I was looking through this the other day and found an interaction with my daughter when she was about 6 and my son when he was about 8. We were walking in Aldinga Scrub, and my daughter suddenly declared, “The bush is a story.” I asked her what kind of story, and she replied, “A wild story.” My son followed with, “A lucky story, because no one’s turned it into houses.” My daughter then said, “It’s an easy story, because you don’t have to water the plants,” and the exchange went on with both of them thinking of all the kinds of stories they could imagine from that patch of ground.

Today I want to share with you some of the stories of the patch of ground we call Yarnauwi. I acknowledge that our story sits within a web of stories that started millennia before the brief glimmer of our lives, and that there are many more stories that will follow. Most significantly, I acknowledge the connection of the Kaurna and Ramindjeri people with the region we call home. Their ancient and enduring management of the landscape, their story, remains the only proven model of sustainability for this region.

In the spirit of the Convergence theme of “Thriving Together”, I also want to acknowledge that this story is one that has only been possible through the support and hard work of our community of friends and family.

Finding a farm

Sophie and I came to permaculture via community environmental groups. We were working with community environmental groups on a range of issues before being drawn to local community food systems. I came across permaculture through a chance encounter in the early 2000s, and completed my PDC at the Food Forest in 2006. In 2009, Sophie and I spent 9 months travelling overland from northern British Columbia to Nicaragua, visiting community food initiatives and permaculture projects and working on farms and ranches. We returned inspired, but also ready to start putting some of the things we had learnt into practice. We were at that time planning to develop and run a small farm, and so started looking for land. After a few false starts, we found 19 hectares near Second Valley.

It was, in the old real estate adage, “the worst block in the best location”, a denuded single paddock with erosion gullies filled with dumped rubbish and two trees. It was part of the “Anacotilla” station that once extended from the Gorge at Lady Bay to Second Valley and had been divided into several smaller farms. Yet despite the sense of isolation and neglect, it was also less than a kilometre from the sea as the black cockatoo flies, set in a bowl of hills beneath the vast dome of the Fleurieu sky.

So we signed the papers, after which the lending advisor gleefully told us, “You realise that “mortgage” means “dead pledge”, it’s a debt you have until you die! Ha ha!” If that wasn’t terrifying enough, we quickly realised we were way out of our depth. We were suddenly chillingly aware that we were now perched precariously in the middle of countless visible and invisible natural processes that we had neither the knowledge nor the capacity to manage. Visiting on the weekends with a young child, a wheelbarrow and a few hand tools, the place felt like it was spinning out of our control. Plants grew, rain fell, erosion gullies marched uphill, sinkholes formed, kangaroos grazed in their hundreds.

This was a period that I think of as “The Age of the Post-Apocalyptic Picnic”: Saturdays spent in a collapsing sun shelter in a baked and windswept paddock with a baby, trying to balance the stress to “get things done”, while another part of my brain was asking, where is everybody? Why don’t we ever see other people on their farms? How do we actually turn this into a human habitat? Of course, the reason why no one else was out was obvious. Even putting aside the gale-force winds and blazing sun, no one was out for the same reason people don’t tend to have picnics in factories, mines or landfill sites. It was an industrial landscape, its purpose was not to be a home for anything, but to extract resources.

A realisation that came later was that permaculture is a process of telling a different story about place, from industrial and extractive to a home for both human and non-human communities, thriving together.

Observe and interact

There’s a quote from literature scholar Brian Elliott about the how environmental consciousness might develop among non-Indigenous Australians: “At first the urge is merely topographical, to answer the question, what does the place look like? The next phase is detailed and ecological: how does life arrange itself there? The third phase may be moral: how does such a place influence people? And how, in their turn, do the people make their mark upon the place? The final phase involves subtler enquiries: what spiritual and emotion qualities does such a people develop in such an environment? In what way do the forces of nature impinge on the imagination? How do aesthetic evaluations grow? How may poetry come to life in such as place as Australia?”

I like how this reminds us of the culture part of permaculture, that we are engaged not just in a project of building gardens, but of establishing a culture of connection to landscape and each other.

We were living an hour away, and would visit each weekend, doing things like pulling rubbish from gullies, or otherwise trying to get to know the place. Our learning curve was so steep as to be vertical. This distance was beneficial. It taught us, slowly, that, actually, little to nothing was in our control, and that everything we did would and should only happen at the pace of the ecosystem. That was a good realisation.

This distance also allowed us to go deep in researching the history and ecology of the landscape, combining our research with our own observations, in the spirit of the permaculture principle of “Observe and Interact”.

We began with a “One Page Place Assessment”, a document inspired by permaculture rainwater harvesting guru Brad Lancaster. This allowed us to compile available data on key water and landscape characteristics in one place, then to compare this with our own experiences. One of the things I loved about this process was what Lancaster calls “Totem Species”, species currently or historically present in the region, which you can design for. What are the needs of an echidna or a black cockatoo? How do we get from a paddock to somewhere a scarlet robin would live? This thinking was transformative for me.

In the spirit of long and thoughtful observation, we began documenting everything we noticed or saw. We began with a spectacular but impractical circular calendar, divided into seasons, then observations about weather, animals, plants, soil and water. This evolved into an ongoing family nature notebook. For myself, nature journaling remains a valuable practice for observation, questioning, research and contemplation. Over time, these practices have helped us to see seasonal patterns or deviations, but also to understand the connections between natural phenomena – for example, which birds appear when grasses are in seed.

We had an idea of this place as a diverse small farm and restored habitat, but realised that to understand its limits and potentials, we needed to go into its history.

A template from history: First Nations land management

At the time of colonisation, what is now Yarnauwi was part of a corridor of open blue gum woodland, growing on the deep soils between the coastal cliffs and the shallower soils of the highlands. Colonists were thrilled at the agricultural potential of this landscape and quickly took advantage of it.

If we look at early colonial depictions of the landscape, we can see this pattern of open country, with wooded hills. This of course was a landscape cultivated through human intervention and particularly through the use of fire. Through fire, the Kaurna and other First Nations could not only reduce fuel load, but also create a mosaic of different habitats, create forage for game, germinate fire dependent species or protect fire-sensitive species, protect special areas, open country for travel and maintain areas for the cultivation of yam daisy and staple grains such as kangaroo grass. Our understanding of how the landscape was managed by the Kaurna and Ramindjeri and the richness of the pre-colonial landscape has been informed by the work of Bill Gammage, Bruce Pascoe, Don Watson, Philip Clarke and others.

Yarnauwi is part of a landscape that is still rich with Kaurna and Ramindjeri memory and culture. The name “Yarnauwi” was given to us by Kaurna Warra Pinyanthi, the Kaurna language keepers, as a reference to the locality it’s part of, “Yarnauwingga”. Five hundred metres from our back boundary was a meeting place, documented in colonial accounts as a place of massive gatherings for First Nations people. Keep going to the coast and you’ll find a burial cave, excavated by archaeologists in the 1930s, in which the preserved body of a woman was found laid to rest in a slate-lined tomb. The caves and springs of the area form locations of the Tjirbruke Dreaming Track.

This was a way of life guided by a deep understanding and meticulous observation, including seasonal movements from the hills to the coast to harvest and conserve resources. I recommend the work of James Tylor who provides much greater insight into this. He has a great article in CityMag and a video on YouTube about the Kaurna diet.

A glimpse of the depth of Kaurna knowledge of their landscape is seen in the Kaurna seasonal calendar, represented by Scott Heyes. Instead of seasons being fixed according to dates, as in the European calendar, the Kaurna calendar had 4-6 seasons, that would begin once a critical mass of environmental phenomena had been reached.

Why is this important? Firstly, it provides a precedent for the potential of this landscape to thrive and function as a diverse mosaic of species and functions. It also reminds us how observation is the foundation for care of place.

Mistakes to avoid: colonial impact

The first Europeans to colonise South Australia came to an unfamiliar land and climate, and initiated profound changes in the landscape. Landscape ecologist Sophia Bickford asserts that their change was such that the landscape and ecosystems that exist now are considered entirely new ecosystems, due to the loss of indigenous species, the introduction of new species and substantial changes to the function of the landscape.

By 1840, there was a small population of British subsistence farmers living in the region. Their impact was immediate and over the successive decades, the landscape went through a sequence of extractive uses. First land-clearing, beginning in the easily accessible blue and red gum woodlands, cropping, grazing, wattle-bark harvesting and so on.

While Aboriginal burning patterns ended with European arrival, burning actually increased, with landscapes burnt every five years or less to open the country for farming and grazing. This would have rapidly eliminated fire sensitive species from many areas of the landscape.

These changes resulted in an eroded, deforested and desertifying landscape. Landscape historian Sophia Bickford writes that the impacts of colonisation are still in play on the Fleurieu and that ongoing land uses are preventing regeneration and therefore “new ‘stable’ ecosystems have not yet been formed”.

Trees

While Kaurna and Ramindjeri land management practices cultivated a diverse and complex landscape, the colonial land clearing unleashed a cascade of unforeseen consequences.

Let’s talk about how erosion happens.

We start with a landscape with trees and vegetation. This protects the soil from rain fall, slows and spreads water flows and manages water in the soil by drawing it up into the vegetation and the roots binding the soil together.

Remove these through land clearing and grazing and water begins to flow over unprotected soil. Water concentrates in folds and hollows in the landscape and gathers momentum and energy. It starts moving soil and deepens these hollows into channels.

A hydrated landscape, where water is held in the soil, become a dehydrated landscape, where water drains off quickly through the erosion gullies.

Trees don’t just hold water in the soil. Trees – and particularly forests – are increasingly understood to increase water availability as a whole. There is a growing understanding that “rain follows forests” – trees act as an “atmospheric moisture pump” that carry water from oceans inland. Research from Zurich University has supported this, suggesting that increasing Europe’s forest cover by 14% could increase the continent’s overall rainfall by 7%, including in desertifying Mediterranean regions.

It’s not just about rainfall, but also the role trees provide in generating and harvesting moisture from mist, snow and low cloud.

A farmer at Parawa once described to us how he recalled the winters of his childhood as being defined by constant mist and drizzle. Other accounts note the importance of low cloud and mist being harvested by the forests of the Mount Lofty Ranges, providing a significant supplement to rainfall (let alone historical snowfall). In contrast, Fleurieu winters seem to be shifting more towards a pattern of clear skies and discrete rainfall events, rather than constant low cloud.

While forests contribute to the big scale of the water cycle, trees are also important in local water cycles, where moisture moves through a landscape on a very small scale, perhaps even the scale of individual trees.

These trees and the green circles of grass underneath them show how this might work. The tree harvests moisture from mist and provides a protected microclimate for moisture in the soil underneath. The grass grows and transpires, increasing the humidity in that very local area. This is an important function of local water cycles, they are critical in stabilising temperature extremes between day and night and from season to season.

How does this apply to us?

We know that our landscape was wetter in the past. This change is undoubtedly due to climate change, but I would also argue that deforestation is a factor. Colonial accounts from around the world have documented sharp drops in rainfall following land clearing. In our own context, in the 1860s, it was typical to have a rainfall of 800mm in our area. This is now down to about 450mm.

Our scale is too small to effect profound change across our region, but our revegetation efforts are already having an impact on stablising the landscape and restarting the local water cycle.

Property planning

With this in mind, the easiest part of our property planning was identifying our Zone 5, or “wilderness” zones. We needed trees. The fingers of erosion gullies that extended into the property were in desperate need of stabilisation. Trees to manage water in the soil and on the surface were essential for this. With assistance from the Natural Resource Management Board, we began by fencing off these areas.

We then planned inwards to Zone 1, planning shelter belts, woodlots, possible house and shed sites, and their associated gardens and orchard plantings. With further support from the NRM Board, we gradually fenced smaller paddocks, with the view to establishing windbreaks and practicing managed grazing.

The plans changed and evolved regularly. Having multiple blank photocopies of the farm boundaries and key features and packet of textas was invaluable for imagining and reimagining as we learnt more about this place. Maths exercise books are fantastic for planning, and we’ve used them throughout for mapping, property planning, and house and garden design.

In the early stages, we maintained very formal farm plans which identified short, medium and long term goals, together with budgets and projected income and actions for each year. These were useful in the early stages to try to break down the scale of the project into manageable chunks.

Over time we also incorporated elements of the Holistic Management approach, articulating holistic goals and so on. These holistic goals still remain mostly true, and were crucial in helping with decision making as the project progressed. However over time our focus has shifted more towards biodiversity regeneration, particularly shaped by personal capacity and observations about what will be best for the land.

Revegetation

In our first winter, we planted 1000 trees in our future “Zone 5” with our community of friends and family. Most failed, devoured by deer, kangaroos or inappropriate placement. So we sought out remaining patches of forest nearby to try to learn the preferred soils and aspect of particular species.

The next year, we tried again with another 1000 and our friends and family returned to help. Amazingly they continued to do so, year on year, even when we couldn’t. I’m in such awe of our community that returned each year, even when progress was not evident.

We tried new approaches with the kangaroos, some practical and some philosophical. Sophie refined tree guard designs while I attempted to speak to them and explain the project and our intentions to recreate habitat. Eventually, with kangaroo impact so intense that it was creating erosion channels, we resorted to a small cull and the trees had an opportunity to take hold. They were largely invisible, waiting in their guards for five years, but eventually gathered their own momentum. The pace of the ecosystem.

While we prioritised local indigenous species in our habitat restoration, we have also sprinkled the plantings with species from climate zones further north in anticipation of the southward shift of climate change. Similarly, some areas of the property were so profoundly changed through almost two centuries of cultivation, chemicals and grazing that local species no longer tolerated the conditions. These areas we planted as coppice woodlots for timber and firewood, selecting species from drier climates with similar soils. As an experiment, we have also selected species in some of these areas that bare the soil, so when combined with high pruning will hopefully create a living firebreak. These species have boomed.

Erosion control

Our soils have the unfortunate characteristic of being dispersive. This means that in some sections of the property, while the topsoil is relatively stable, the subsoil has a chemical composition that means it dissolves when saturated and begins flowing underneath the topsoil. Often the first you see of this is a sinkhole, usually with a tunnel that flows out somewhere else. Eventually the tunnel collapses and you end up with the brand-new erosion gully.

At the time, it seemed that much of the conventional erosion control methods were costly and energy intensive. We were keen to find a more permaculture approach: small interventions based on observation that used local resources.

Peter Andrews and the Natural Sequence Farming approach offered some guidance, but the most valuable information for our context was from the work of Brad Lancaster, Craig Sponholtz and Bill Zeedyk, from the arid southwestern US. All have outstanding, practical resources based on the philosophy of “letting the water do the work”.

Based on their work, we developed a method of reshaping actively eroding areas by hand back to a less erosive “angle of repose”, adding gypsum to address the chemical structure of the subsoil, armouring the surface with stone or concrete demolition rubble salvaged from gullies and then broadcasting native seeds.

In other areas, Zuni Bowls helped to disperse the energy of water flows, while One Rock Dams in gully floors slow water and catch sediment, incrementally lifting the gully floor. If or when these methods fail, they are easily fixed. They require patience and observation, some, like the One Rock Dam, require “upgrades” over time to continue to lift the gully floor, while others, like Zuni Bowls or Rock Mulch Rundowns, will eventually disappear into the landscape.

Combined with the revegetation, these erosion control strategies have allowed us to plant the water back in the soil. We have a dam that rarely fills now. However, what rain we do get is held in the soil, is held in vegetation and is being cycled through the landscape.

In summer, you can feel the local water cycle at work when you walk towards an emerging patch of woodland on a warm, dry summer evening and feel the temperature drop, and humidity gather around your feet. You can smell the scent of rain on soil as you approach, even when its hasn’t rained in weeks.

Processes in motion

Establishing revegetation and making interventions like erosion control were a process of setting up the biological infrastructure to try and tip the landscape away from desertification and towards a cooler, wetter, more abundant place. With a bit of initial care, they are processes that eventually manage themselves and generate their own momentum towards a different state.

In the first couple of years we saw an explosion of weeds. It reminds me of when Allan Savory describes the landscape as a coiled spring. Conventional land management, which tries to simplify a landscape into a few easily managed variables, regularly compresses the spring and increases instability and fluctuation through the removal of species. When the management changes, as it did with us, the spring unfurls, sometimes bouncing uncontrollably as the energy of the previously suppressed processes are released. For us, we saw entire paddocks overrun with wild mustard, almost head high. We mowed a bit and tried to work out what the mustard was telling us.

In our research, we came across the work of Vail Dixon, who talks about the role weeds are playing in landscapes. Her work focuses on cultivating the conditions for what you want to create, highlighting that focusing on a problem can often simplify the system exactly when we want to increase complexity. She looks at the relationships between soil food webs and their fungi and bacteria ratios and above ground vegetation.

To create habitat, restore woodland and establish orchards and woodlots, we saw that we probably needed to create a more fungal environment, rather than the bacterial environment of grassland. We also realised that if we were working to create a more stable, self-managing system, we needed to move away from the strategies that had been used previously.

One of Vail Dixon’s catchphrases is “What you resist, persists!” So, rather than fixating on wild mustard, how did we begin to create the conditions to tip some sections of the farm towards woodland and thus diminish the conditions for this species?

- Some of our management looked at how we can limit its growth, including strategic slashing (ideally when it was still green and leafy, rather than tall, fibrous and seed-producing) and allowing the cut plants to form a mulch layer. We also tried grazing a strategic times, with varying success.

- When establishing woodlots and orchard areas, we would mow, then lay thick mulch berms along the contours of the area. These berms of woody mulch would hold moisture, protect the soil, promote fungal conditions and were thick enough to eliminate germination of the mustard. We planted directly into these. In some of the most exposed and hostile areas of the property, these berms were the catalyst for trees actually surviving.

- We augmented the soil with compost, including experimenting with cultured compost, to improve soil structure (mustard has a deep taproot to address compaction) and nutrients.

- In some areas, including woodlots, we selected highly competitive species that would outcompete the mustard.

These strategies have been targeted to specific areas that were able to maintain and manage, and were all implemented with the view that ultimately these areas would become primarily self-managing with only minimal occasional or seasonal input from us.

When we had another look at wild mustard, we realised that their deep taproots break up soil compacted by generations of grazing and cultivation, they consume the excesses of nutrients from application of fertilizers, they feed and provide habitat for soil biology (it’s common to find an earthworm tangled in their roots in winter). They also provide abundant bee forage in spring, and unexpectedly for us, eventually provided a corridor for small birds to migrate from the nearby Anacotilla River to our revegetation areas. One element with many functions. Over time, the mustard has gradually decreased in both range and size, suggesting that its time is ending as the conditions become right for other species.

Obtaining yields

Some of you might still have a copy of the classic Australian self-sufficiency book “Surviving in the Eighties”. My favourite page is a bit like a comic, showing the stages of establishing a small homestead, from “The Dream” to the triumphant finale of an abundance of produce and an idyllic country kitchen, captioned “All our own work.”

We’re not quite there yet, but as the momentum of the system increases, so do the yields. This biological infrastructure has allowed diversity and other systems to function.

We’ve tried bees a few times, and now have enough shelter and forage for them to hang around permanently. This year, we harvested our first honey. Fourteen jars of nectar with the spicy tang of wild mustard flowers.

We’ve had a couple of flocks of sheep, and tried different forms of managed grazing. We sold their meat and hides and made things from the leather. There have been some successes, but land management with sheep was not in our capacity to manage in the way we hoped and the sheep have moved on: some to the freezer, some to the local school.

We designed and built an off-grid, passive solar house. The gardens and a small orchard are slowly establishing. We cut down our first tree for firewood from one of the coppice woodlots this year.

Over the last 12 years, our priorities have shifted towards a focus on farm forestry and particularly landscape restoration for biodiversity. When it comes to yields, some of the most satisfying have been those that go beyond the modest harvest of our garden.

Watching trees that you’ve planted is incredibly satisfying, but seeing them function in an ecosystem, providing food and homes and shelter for other creatures and to harvest and hold water in the landscape is almost mind-blowing.

Small woodland birds were always in our minds as target species for the habitat we were trying to create. The paddock we first knew was dominated by birds of open country: ravens, magpies and galahs, with an occasional quail or pipit. After seven years of revegetation, we heard a new call: white-fronted chats. They nested the following year, and then were followed in quick succession by other woodland birds: superb fairy-wrens, pardalotes, silvereyes, fantails, crescent and singing honeyeaters and they keep coming, with almost 60 species now identified. The woodland is returning.

At Yarnauwi, after 6 years of virtually no fungi emerging, in 2018, we began to see a proliferation of wild fungi, many of them mycorrhizal partners for the woodland. Like other indicators, the number of species and their profusion is increasing year on year.

Our work at Yarnauwi has only ever been possible with the support of our community of friends and family. There’s a yield here too, in the relationships forged not only with each other over a mattock and tubestock, but also with the landscape. We’re so thrilled that so many people close to us also have connections and stories that link to this patch of ground. Here too, there is a momentum as Yarnauwi expands as a community space for others to forge a relationship with the land: this year, the Yankalilla Youth Theatre filmed a western in the regenerating gullies.

There’s a landscape restoration group in the US that has a motto along the lines of “where people and prairie restore each other”. I hope that Yarnauwi is, and will always be, a place where community and woodland can restore each other.